Editor’s Note: Dorian wreaked some havoc with my ability to work this week, so I am easing back into regular publication by noting some recent developments in stories I’ve already covered. The bottom line, though, is that I am back, I have bought new school supplies (I am not kidding, I bought a box of pens and one of pencils), I’m working on two interesting pieces for upcoming issues, and Fast & Curious will once again appear regularly on Fridays, as it did before I went on semi-hiatus this summer.

I just heard (then read) the CBC’s Tom Ayers’ report on absenteeism in the Cape Breton Regional Police Services (CBRPS).

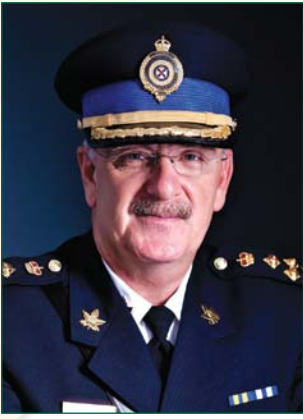

It’s a subject I touched upon back in February, noting that CBRPS Chief Peter McIsaac had recently made the case to council for a police services HR person to act as case manager for all the officers on leave of some description. At the time, McIsaac estimated that, on any given day, this could include anywhere from 15 to 30 officers.

Now, according to what Deputy Chief Robert Walsh told Ayers, that number has climbed to “anywhere between 30 and 40.” And I can confirm — because CBRPS spokesperson Desiree Magnus confirmed it for me yesterday — that Chief McIsaac himself now ranks among those officers on leave. Wrote Magnus:

The Chief is currently off for medical reasons.

Magnus did not respond to a followup inquiry as to how long McIsaac has been out and when he is expected to return.

Walsh told Ayers he had no idea if having up to 20% of your workforce off at any given time was unusual by Canadian police standards — he argued it was the sign of an ageing police force.

Gordie MacDougall, CBRM’s director of HR, claimed that, on average, Cape Breton officers are off the job fewer days per year than most (11 compared to a national average of 12.2) although he didn’t give a source for the figures.

The CBRM has decided to undertake an in-depth study of police staffing as recommended by Grant Thornton in its CBRM Viability Study, which dropped in August.

Viability

In fact, Ayers spoke to Deputy Chief Walsh after Tuesday’s Police Commission meeting during which the Viability Study — and specifically, its suggestion that the municipality’s 200-member police force was ripe for “consolidation” — was discussed.

The final version of the report engendered much agitation, although I personally had worked out much of my agitation in July, when the preliminary version came out. People seemed to respond to the document in one of three ways: either they took it as evidence the province must give us more money, à la CBRM Mayor Cecil Clarke:

Even with an economic development plan, we will continue to lose population at the current rate, which means again, we have to have supports to stabilize and move towards that growth.

Or they saw it as evidence the municipality must learn to live within its means and restructure its departments, à la business consultant and Post columnist Adrian White: “$148 million is enough for CBRM to be financially viable.”

Others (like me) think the future viability of our municipality will require both more money and some restructuring.

And yes, I know that nobody likes a fence sitter.

Bootstraps

In the mayor’s defense, the report itself states quite clearly:

The municipal government’s ability to effectively resolve the region’s issues independently is not realistic.

In White’s defense, the report does find some budgetary fat worth trimming: namely, the above-mentioned police force:

[W]hen assessing the efficiency of delivery, the comparatively high-number of officers, and the fact that the CBRPS has one of the larger department budgets, the CBRPS exhibit qualities that could potentially support consolidation.

I’ve written before about the need to “consolidate” the CBRPS (I honestly think the articles here and here could be helpful to anyone interested in the question), so I was very interested to hear the arguments offered in defense of the CBRM’s over-sized (by Canadian standards) force.

For example, some attribute the CBRM’s low crime rates to its large police force, but my reading suggested there was no real correlation between more police and less crime. The fact is, crime rates have been on a 40-year decline in Canada (and the US) and nobody is entirely sure why, although ageing and declining populations do seem to be factors. It also seems worth pointing out that if 40 of 200 officers are on sick leave, our active police force is actually around 160, which would give us a cop-to-pop ratio similar to that of Hamilton (151), Kitchener-Waterloo (141), Kingston (154) and PEI (153).

White, in his prescription for municipal economic health, goes further, taking aim at the CBRM’s Fire/EMO budget. But at 12% (compared to 18% for the police), Fire/EMO counts for less of the CBRM’s annual expenditures than do mandatory payments to the province for schools, correctional services, public housing and the Property Valuation Services Corporation (13%).

Moreover, White fails to note that while these mandatory payments have risen each year, the operating grants given to less-wealthy NS municipalities have not, leading to a situation in which the CBRM receives $15 million from the province but sends back $19 million (this is another subject on which I’ve written at some length).

Tug on your bootstraps as hard as you like, you won’t make that discrepancy disappear.

I’ll be following this one with interest, but in the meantime, I really must recommend my earlier stories.