On September 24, the Canadian anti-war community suffered a grievous loss with the death, at the age of just 71, of Bill Blaikie, New Democrat MP for Winnipeg for nearly 30 years (1979-2008) and devout Christian believer in a peace on Earth secured not through the chimera of military ‘strength’ but implementation of what we might call the ‘Isaiah Manifesto’:

and they shall beat their swords into plowshares,

and their spears into pruning-hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation,

neither shall they learn war any more.

Blaikie, a United Church Minister, was, in the words of Karl Nerenberg on rabble.ca, “a leading figure in a distinctively Canadian brand of progressive politics, one inspired by a humanistic vision of Christianity”—to which the NDP’s Tommy Douglas and other key figures subscribed—dubbed ‘the social gospel,’ rooted in “a profound belief that the ideology of competition is a lie about the nature of a truly human society.”

Bill Blaikie

One does not have to be a Christian to share that belief; or to see militarism as an ‘ideology of competition’ writ large across the planet; or to agree that the most ‘devilish’ form militarism can assume is nuclearism, the Mushroom Cloud’s threatened triumph of Death over Life. In a March 2022 article, Blaikie recalled growing to political and spiritual maturity under that Cloud:

The baby boomer generation, which I am a part of, was the first generation to grow up with the existential threat to life on earth posed by nuclear weapons. The Cuban Missile Crisis happened when I was in sixth grade. I went back to school after lunch one day not knowing whether we would be back home for supper. What if the Russian ships that were expected to reach the American blockade that afternoon didn’t turn back? What if that led to nuclear war, the war that we had been practicing for, learning how to hide under our desks?

“This anxiety culminated,” Blaikie wrote, in the split atomic decade of the 1980s. First, 1980-85, a nuclear crisis over new Soviet and American missiles in Europe, a red alert inspiring huge waves of protest:

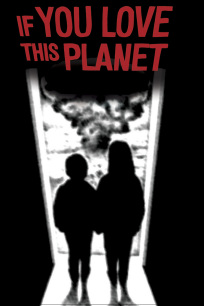

Peace marches proliferated in Canada, as opposition grew to testing Cruise missiles on Canadian territory. The documentary If You Love This Planet, by Dr. Helen Caldicott, was widely viewed. There were municipal referendums declaring nuclear weapons free zones, thanks to the work of Operation Dismantle.

And after the darkest hour, the dawn, the emergence from a semi-comatose Kremlin of a fresh, dynamic leadership whose resolve to escape the fast-closing trap of the nuclear arms race—and, in the process, ‘rehumanize’ the hypertrophied, hypermilitarized Soviet system—was ironically strengthened by nuclear disaster: the catastrophic reactor meltdown at Chernobyl in Ukraine in 1986. For Gorbachev, who later “divided” his political life “into two parts: before Chernobyl and after it,” the accident radicalized both his environmentalism his and loathing of moribund Soviet bureau-technocracy; while around the world, it placed a huge, radioactive cloud of doubt over the so-called ‘peaceful’ uses of atomic energy.

In 1985 Blaikie, seeking to harness a “lively debate in Canada not just about nuclear energy, but also about uranium mining and disposal of nuclear waste,” introduced a pathbreaking Private Member’s Motion demanding a moratorium on nuclear power projects. The battle was lost, but after Chernobyl the political war—with regard to both nuclear energy and weapons—seemed there for the winning.

What happened? On both fronts, as Blaikie wrote, “the debate…died down,” eclipsed by post-Cold War, planet-sized “concerns about global warming and climate change.” Indeed, “for some” (never for him) “the need to reduce carbon emissions argued for more nuclear energy,” at the same time that the specter of nuclear annihilation seemed suddenly, blissfully remote: “Except,” that is, “for those who kept paying attention.”

For a long while, he was one of them. In the late 1990s, he fought a lonely, losing rearguard action against NATO expansion, rightly fearful—as he told a largely empty House of Commons in June 1998—of “committing Canadian forces” to a “defense of new members” likely to involve, “given NATO’s flexible use doctrine…a nuclear  exchange.” That momentous commitment, moreover, was made by the monarchist mechanism of an ‘order-in-Council,’ dispensing entirely with parliamentary debate! As Blaikie, still shaken to his democratic core, told the House in April 1999, this:

exchange.” That momentous commitment, moreover, was made by the monarchist mechanism of an ‘order-in-Council,’ dispensing entirely with parliamentary debate! As Blaikie, still shaken to his democratic core, told the House in April 1999, this:

…was a major decision that was debated in every other parliament of every other NATO country. This is embarrassing. Are we a banana republic run by order-in-Council and executive committee? Even in the UK, where it was not required that they do so, they had a debate in parliament about the enlargement of NATO. … Yet here in Canada we just read about it in the Gazette.

And in the war-torn wake of 9/11, Blaikie worked with peace movement activists to successfully oppose Canadian participation in Washington’s anti-ballistic missile ‘defense’ system, George W. Bush’s cynical power play for nuclear supremacy in the ‘unipolar American world.’

But the attritional effect of an unrelenting lack of political and media attention to nuclear matters began to wear down even such a ‘peace-mongering’ soul as Blaikie, as he acknowledged in his recent rabble.ca piece:

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought many issues to the forefront. Issues which for many, including myself, had lain somewhat dormant for years, losing their edge as the world carried on without addressing their controversial nature.

The ‘edge’ in the post-invasion nuclear energy debate seemed at first to lie with industry boosters, given Europe’s long-standing, widespread dependency on Russian oil and gas. But as Blaikie wrote, “a few days is a long time in environmental politics,” and the ghastly, ongoing crisis about the warzone safety of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power complex and other Ukrainian reactors graphically illustrated the dangers of relying on a ‘peaceful’ technology capable of causing (by mishap or malice) intergenerational mass destruction.

Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant in Ukraine (IAEA Imagebank, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The ‘edge’ in the nuclear weapons debate, too, seemed initially to rest with the wavers of the ‘swords,’ not the prophets of peace. “No poem ever stopped a tank,” Seamus Heaney conceded—and what good would ‘plowshares’ have done, either, in the face of Moscow’s onslaught? Indeed—this peace-through-strength argument runs—in the atomic age, no tank can ever stop the Bomb, so when it comes to ‘swords,’ don’t we need The Big One on our side? Isn’t that thermonuclear ‘insurance’ exactly what Finland and Sweden promptly sought, rushing headlong into NATO? And if Ukraine itself had been in NATO—or hadn’t surrendered its Soviet-era ‘Big Ones,’ in return for worthless security guarantees—wouldn’t it today be secure, whole, and free?

To pan in on Ukraine, the version of events suggesting that its nuclear disarmament was a “blunder” and “stupid mistake,” is, as Mariana Budjeryn from Harvard Kennedy’s Belfer Center writes, “a facile narrative that omits important facts.” Ukraine had no legal ‘right’ to the weapons, never owned or claimed to own them, and thus did not ‘surrender’ them. (South Africa is the only state in nuclear history to dismantle its own arsenal.) Nor would Ukraine, or the other nuclearized former Soviet republics of Belarus and Kazakhstan, have been allowed—by Moscow or Washington—to claim them. But neither did Ukraine want them, instead declaring, as early as 1990, its intent to become both non-nuclear and neutral, inspired in part (to quote Budjeryn’s understatement) by “the general antinuclear sentiment sparked” by Chernobyl.

The 1994 Budapest Memorandum—signed by Ukraine, Russia, the UK and US—offered no ‘guarantees’ of intervention if Ukraine was attacked, but rather non-binding ‘assurances’ of political and other support. That Russia annexed Crimea, 20 years later, was the grossest conceivable violation of the letter and spirit of the Memorandum. But if NATO, shortly after the Memorandum was signed, had not started to flow east to Russia’s borders, breaking promises and trust along the way—if the Memorandum had served as the diplomatic bedrock of a neutral Ukraine—would the same, tragic history have unfolded? Though it is increasingly controversial to say so—as if seeking to explain something equates to excusing it!—the many seeds of the whirlwind were not all sown by one side.

Protestors at anti-war rally in central London, 6 March 2022. (Alisdare Hickson from Woolwich, United Kingdom, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

We also need, though, to pan back, for if most of the world rightly condemns President Putin’s nuclear ‘sabre-rattling,’ does that mean it thinks NATO is entitled to wave its own sword? Is the international community right to think the ‘Big One’ has emboldened Putin’s conventional violence, but wrong to think it emboldened America’s far more catastrophic invasion of Iraq, and its other, innumerable ‘special military operations’ since 1945?

Of course, the great majority of the world’s states and peoples understand that the calamity now befalling Ukraine, and threatening daily to engulf us all, is a clinching argument for the kind of deep détente and disarmament rendering such bloodbaths politically unthinkable, strategically illogical and practically impossible.

The Isaiah Manifesto, lest we forget, has two parts: converting the swords, and unlearning how to wield them. Conversely, possessing the nuclear sabre involves studious preparations for its actual use. Rest assured, our nuclear deaths will be highly practiced ones: fine-tuned, in fact, in just the last few weeks in war games by NATO and Russia. On October 17, despite numerous appeals for a delay or cancellation, NATO’s annual two-week Doomsday Dress Rehearsal—titled, like a Western, Steadfast Noon—opened as scheduled, overlapping with Russia’s yearly Grom (Thunder) refresher-course in Grim Reaping.

B-52H Stratofortress. (Photo by Tech. Sgt. Heather Redman/U.S. Air Force, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Grom, according to the Federation of American Scientists’ Hans Kristensen, on October 14, “will practice deployment of strategic nuclear forces and possibly include test launches of nuclear missiles,” while Steadfast Noon “will exercise the tactical nuclear fighter wings in Europe and their ability to deliver US B61 nuclear gravity bombs.” The latter involved 14 nations (including Canada) and 60 aircraft, converging on Kleine Brogel airbase in Belgium, one of six bases—two in Italy, one in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and Turkey—housing around 100 B61s, each up to one-third as powerful as the 15-kiloton bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Tellingly, Steadfast Noon also featured what Professor Michael Klare calls that “iconic US instrument of nuclear combat and coercion,” the B-52 ‘Stratofortress,’ flown in from a strategic bomber base in North Dakota. Kristensen was struck that the B-52s were, unusually, “mentioned explicitly” in NATO’s announcement, presumably to enhance “deterrence signaling” at this time of tripwire tensions.

But doesn’t it also signal that attempts to ‘limit’ a nuclear exchange are—despite all these extravagant, expensive practice runs—likely doomed to fail? Or, as Isaiah—and, no doubt, Blaikie in his darkest moments—foresaw:

Your country lies desolate,

your cities are burned with fire…

Postscript

In last December’s War & Peace column, I explored the idea of a Canadian Citizens’ Assembly on Nuclear Disarmament, convened by parliament and empowered to make recommendations related to Canada’s commitment to achieving a Nuclear-Weapon-Free World. On August 6—Hiroshima Day—Peace Quest Cape Breton (PQCB), a nonpartisan citizens’ group I am proud to belong to, issued a Concept Paper on the proposal, followed on September 21—UN International Day of Peace—by the release of a ‘Model Assembly’. The initiative has already been endorsed by groups including Conscience Canada, Voice of Women (VOW) for Peace Nova Scotia, the Canadian section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) and individuals including Hiroshima-survivor Setsuko Thurlow, co-recipient of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). This autumn, PQCB is approaching a wide range of political and public figures, seeking their help in kindling our local flame into a national campaign.

Bill Blaikie was high on that list.

Sean Howard is adjunct professor of political science at Cape Breton University and member of Peace Quest Cape Breton and the Canadian Pugwash Group. He may be reached here.