On numerous occasions in recent decades, Canadian governments have apologized for a host of egregious wrongdoings.

While such words of contrition are too often unaccompanied by adequate actions, they can help make visible, as Trudeau argued in his 2017 apology, the “hard truths” Canadian society needs to confront.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivers a statement of exoneration for Chief Poundmaker, May 23, 2019, Poundmaker Cree Nation. photo: Adam Scotti Prime Minister’s Office

Yet the most extraordinary apology in Canadian history was surely that offered by the victims of systematic mistreatment by the Canadian government to the victims of a crime against humanity they unknowingly helped others commit. For on 6 August 1998, 10 members of the small Sahtúgot’ine Dene community of Déline (Fort Franklin) in the ‘Northwest Territories’ apologized in Hiroshima for the atomic destruction of that city – and the death of over 200,000 civilians – exactly 53 years earlier by a bomb made in part from uranium from their land.

The Dene didn’t even mine the stuff, a role reserved for the all-white below-ground workforce of Eldorado Gold Mines Ltd., placed under state control during World War Two. They were allowed only to help it on its long and winding way, 3,000 miles by river, lake, road and air, from Port Radium on Great Bear Lake to Port Hope on Lake Ontario, where, from 1942-45, the suddenly precious ore – the ‘new gold’ of the atomic age – was, together with ‘Belgian’ uranium from the Congo, refined and dispatched to Los Alamos, the desert lab in New Mexico secretly building the new, city-smashing Superweapon.

There, as Concordia professor Peter van Wyck chronicles in his 2010 study The Highway of the Atom, it “made its transformed debut at Alamogordo,” site of the Trinity test of 16 July 1945 (‘The Day the Sun Rose Twice’, an “entrance reprised shortly afterward, over the clear morning skies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

Hiroshima 1945 By US government Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The existence of this epic road to hell was unsuspected by the Dene until long after Eldorado stopped mining for radium and uranium in 1960. Beginning in the 1970s, and spiking sharply in the 1980s, many of the men who had handled and carried the ore – and the men who had mined it – began to die from cancer, raising obvious questions about health and safety which soon led in shocking directions.

In the 1990s, Gordon Edwards, co-founder of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility (CCNR), told a group of Déline Dene there was compelling evidence that the ore that had made so many of them sick had been used to kill vast numbers of innocent people. By the end of decade, Déline was better known as The Village of Widows, the title of a film by Peter Blow, documenting not only the toll on the community but its extraordinary Hiroshima pilgrimage.

The Village of Widows was broadcast on the Canadian Vision channel in 1998; the following June, without mentioning the film, CBC News announced it “has learned about a dark chapter in Canadian history,” a scandal surrounding “the raw materials used to make the atomic bombs that fell on Japan.”

The “Dene,” the CBC ‘revealed,’ “were never told of the health hazards they faced, even though the government knew … as early as 1932 that precautions should be taken in handling radioactive materials”. Instead of which, for example:

“Paul Baton, now aged 83, used to lift sacks of uranium ore onto boats. He said workers dressed in casual clothes and uranium dust ” — gold dust yellow — “covered the men like flour.”

‘Paul’ Baton was actually Peter Baton, interviewed by scholar and playwright Julie Salverson for her Lines of Flight, an Atomic Memoir published in 2016. Peter’s wife, Theresa, told her:

…that when they lived in Port Radium, the women would make tents for their families to sleep in from the sacks that carried the uranium.

The image harrowingly evokes the poverty of the workers, as detailed in a December 1998 article, ‘Déline Dene Mining Tragedy,’ in First Nations Drum:

During the beginning of the war efforts, the mine was kept running at a very high pace, utilizing non-Native miners brought in from all over the country. The Dene were employed as ‘coolies’ packing 45-kilogram sacks of radioactive ore for three dollars a day, working 12 hours a day, six days a week.

This at a time when the ore was worth over $70,000 a gram.

An unidentified man stands by stacks of pitchblende concentrate awaiting shipment at Port Radium in 1939. Photo: Richard Finnie via NWT Archives

Cindy Kenney-Gilday, a member of the delegation to Hiroshima and Chair of the Déline Dene Band Uranium Committee, told First Nations Drum journalist Ronald B. Barbour that the toll taken on “my own home” is “the most vicious example of cultural genocide I have ever seen.”

“Kenney-Gilday,” Barbour wrote, “who has suffered the loss of her father to colon cancer and brother to stomach cancer, stressed that” because “it is the grandfathers in Dene society” who traditionally transmit teachings and worldways to younger men and boys, “the loss of these men in the community” has left “too many men” without guides.

The guide to all Dene, of course, is the land itself, and the legacy of the Eldorado era has been to create “a radioactive heartland.” Wrote Barbour:

Over 1.7 million tons of radioactive waste and tailings was callously dumped into and around the lake, drastically contaminating food sources.

Kenney-Gilday, though, was keen to stress the link between the local and global tragedies involved. In Hiroshima, she told Barbour:

One of the widows expressed deep sorrow that the material that came out of our land had killed innocent victims in a land that’s foreign to us.

In 1998, the Déline Dene Band Uranium Committee released a 160-page, 14-recommendation report, “They Never Told Us These Things.”

In a 2011 article in Maisonneuve, Salverson recounts a community meeting in Déline to discuss the report, “where [non-Dene] lawyers delivered a year’s worth of uranium-impact research from the archives in Ottawa,” revealing that in “the mountain of papers we dug up … there is not one mention of the Dene, your people.”

“The hall,” Kenney-Gilday remembers, “went completely silent. The elders had incredulous looks on their faces, a combination of sadness and anger.”

Nor were they once mentioned in Eldorado: Canada’s National Uranium Company, the official company history commissioned from University of Toronto historian Robert Bothwell in the early 1980s as controversy grew over the criminal negligence of Eldorado as both as a private and Crown corporation.

Van Wyck quotes a 1986 review, noting that:

[A] company history is often a sign of trouble. It frequently signifies the passing of a generation of managers, the need to clean up the company image after a corporate catastrophe, or the loss of institutional memory. Increasingly, corporate histories are now being written as part of a long-range planning process. This book by Robert Bothwell is an example of all of the above.

The pernicious result, as van Wyck laments, is that despite its abject failure to “consider issues of health and safety or Aboriginal involvement,” or to draw “comprehensively” on company archives now under lock-and-key in Ottawa, Bothwell’s account – “the work of a single author under a contractual arrangement with a corporate body” – has “come to constitute the field of historical facts for all questions pertaining to Eldorado.”

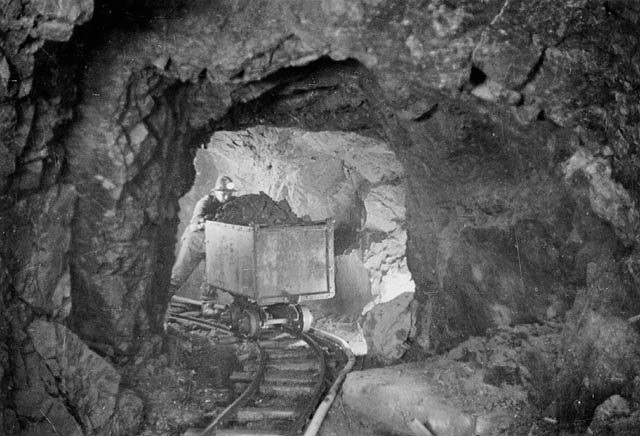

A miner hauling a car of silver and radium ore, 340 feet below the surface, at the Eldorado Mine of Great Bear Lake. c. 1930. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

In 1999, the Ministry of Indian Affairs and Northern Development appointed a Canada-Déline Uranium Table (CDUT) to investigate ‘health and environmental issues relating to the Port Radium mine.’ In 2005, its final report, while acknowledging “the perceptual link between exposure to mining activities and illness and death,” found no evidence of abnormal cancer rates in the area; it also concluded that the numerous environmental “impacts” and examples of contamination it considered were “not a cause of concern from an ecological perspective.”

The findings, Salverson writes, drew fierce criticism from “both inside and outside Déline”: “Well-known environmental journalist Andrew Nikiforuk,” who had been studying the issue for years, “expressed concern that the study’s narrow framing weakened its findings,” while “Intertek, the official fact-finder hired for the CDUT report, was not able to access key archival information” – the very information, perhaps, that had so disinterested Bothwell.

Most controversially, the “only statistics considered relevant in the determination of cancer were body counts,” with other easily-obtainable, highly-pertinent evidence (e.g. blood and urine samples) excluded, despite the report’s own admission that “cancer statistics should be interpreted cautiously because of gaps in the NWT cancer registry prior to 1990 and the small populations in both Déline and the NWT.”

As van Wyck notes, in a 2006 documentary on Déline – David Hennington’s Somba Ke: The Money Place – scientist and anti-nuclear campaigner Dr. Rosalie Bertell argued that relying “on death records alone” effectively killed off the study: “Yet again,” he writes, “the testimony of their dead has proven insufficient. Once again, the living are passed over in silence.”

In a 2008 CBC radio documentary, Bothwell claimed that uranium from the Eldorado mine was not used in the bombs dropped on Japan, basing his conclusion – that only the higher-quality ore from the Congo was needed – on documents seen in the course of his 1980s research. Although such documents might be among those the Déline Dene are barred from viewing, it seems odd that Canadian government agencies should either not know or would deliberately exaggerate the extent of the country’s wartime role. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), for example, provides the public with a presumably well-informed summary of ‘Canada’s Historical Role in Developing Nuclear Weapons’:

The extraction and processing or uranium as well as research into the production of nuclear materials for military purposes are part of Canada’s history. The better-known chapter of that history is probably Canada’s participation in the Manhattan Project … when our country supplied and refined uranium for use in US facilities.

On 6 August 1945, C.D. Howe, Canada’s Minister of Munitions and Supply and Reconstruction, issued a statement – or what van Wyck called “a terrifying sociopathic analysis” – arguing “the real significance” of Hiroshima was not that “this new bomb has accomplished an almost incredible feat of destruction, important as that fact may be,” but that “the bomb is a sign in which we can all appreciate that the basic problems of the release of energy by atomic fission have been solved.”

A week later, responding to “widespread interest in the work carried on in Canada,” Howe’s ministry provided more details of ‘Canada’s Role in Atomic Bomb Drama,’ including naming the 89 Canadian scientists (eight of them women) employed at a hitherto-secret atomic research laboratory in Montreal. Howe himself – who offered the Americans “Alberta’s wide-open spaces as a test site for the new weapon” – stressed that:

…having ample supplies of basic materials, good water supplies, and isolated sites well suited to the work, Canada … has been able to enter as a pioneer into an important new field …

Yet how well-known is this history today? In Lines of Flight, Salverson recounts her first contact with such facts, a phone call from her friend Peter van Wyck: “Did you know,” he asked, “that the uranium used to develop the atomic bombs dropped on Japan came from a uranium mine in northern Canada?” “No, she admits, “I didn’t. Nor did most people, I would later learn. Somehow this was left out of our public school curriculum.”

Van Wyck himself only learned from watching Village of Widows: for both, Canada’s contributions to the greatest ‘drama’ of modern history were Things They Were Not Told. (The extent of this ‘erasure’ will presumably have varied widely in time and place over the atomic age, and I welcome any feedback from Spectator readers on their own experiences as teachers or students.)

A sign with a jar of fused sand from the first atomic bomb. source: NWT Archives

In 2015, van Wyck wrote of the Dene apology : “how is it that one comes to assume responsibility for that over which one has no control. How? How in the midst of recognizing their own disaster, did they attend to the Japanese survivors? Struggle though I have, I cannot answer this question.”

One factor, I suspect, is the fact the Dene were warned by the 19th century prophet and medicine man Ehtseo (Louis Ayah), that the Somba Ke rock – future site of the Eldorado mine – would become the source of great evil. As told in George Blondin’s 1990 collection, When the World was New: Stories of the Sahtú Dene, Ehtseo recounted a vision of “people going into a big hole in the ground – strange people, not Dene. Their skin was white…and they were going into a hole with all kinds of metal tools and machines.” Then “I saw”:

..big boats with smoke coming out of them, going back and forth on the river. And I saw a flying bird – a big one. They were loading it with things… I watched them and finally saw what they were making – it was something long, like a stick. … I saw what harm it would do when the big bird dropped this thing on people – they all died from this long stick, which burned everyone. The people they dropped this long thing on looked like us, like Dene. … But it isn’t for now; it’s a long time in the future.

And ‘for now,’ in They Never Told Us These Things, we have the acknowledgment of the Déline Dene not only that “we are suffering intense grief…that the materials we carried to the barges and to the aircraft went to make an atomic bomb that killed many tens of thousands of human beings in Japan,” but that “our people feel that if they been told what they were helping to do, they would not have done it”, surely suggesting the apology was intended in part to convey – perhaps to themselves, and future generations, as well as others – that given the chance they would have shown sufficient humanity, to resist such inhumanity. That they would today be able to say, as Chief Poundmaker proudly declared in 1885: “I did everything to stop bloodshed. If I had not, there would have been plenty of blood spilled…”

The hard truth is that no apology can ‘unspill’ blood, no confession undo a crime. But does that mean the Prime Minister should not say sorry, in Déline and in Hiroshima?

Sean Howard is adjunct professor of political science at Cape Breton University and member of Canadian Pugwash. He may be reached here.