You probably just read Part I of this P3 Hospitals article, but in case you then took a juice break, or a yoga break, or a few minutes to breathe deeply or pound a couple of shots of tequila, let me remind you why, according to Premier Stephen McNeil, his government opted for a private-public-partnership (P3) approach to the QEII Health Sciences Centre redevelopment project rather than what’s known as a public sector alternative (PSA).

According to media reports (specifically this CBC story and and this one), McNeil said:

- “We have not built something like this in our province in a very long time, if ever.” It’s one of the key reasons the government opted to go with the P3 model, said McNeil. The government believes it gives the greatest certainty for work to be done on budget and as ordered.

- The premier said P3 also gives the government more flexibility for continuing with the rest of its capital plan for projects such as schools and roads.

- Inside government…officials are working with outside consultants. The government wants to make sure, unlike the school contracts, the details are spelled out and responsibilities are crystal clear — down to the exact size and speed of hospital elevators.

- [An official closely associated with the project]…said the job of monitoring the maintenance contract, to ensure promises made were kept, would fall to one of three government entities — either the Nova Scotia Health Authority, Nova Scotia Lands or the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal.

And here’s what David Jackson, a spokesperson for the Premier’s Office, told me when I asked what the reasoning behind the choice was:

The P3 approach will ensure greater cost certainty by putting the responsibility for any cost overruns with the private sector, not the province.

Okay, let’s consider those reasons in detail.

Qualified bidders

Even from the very start of the process, there are often a limited number of private consortia equipped to bid on major [P3]s, which already leads to the potential for bidders to build in higher profits, and thus, higher costs for taxpayers. (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

This first reason the government has given for opting for a P3 model — the sheer size and complexity of the QEII Health Sciences Centre project — is an equally effective argument against opting for a P3 model.

As Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining point out, tendering a large, complex project immediately limits the number of private consortia that can bid on it. And as we’ve noted, the QEII P3 agreement will be a design-build-finance-maintain model, which is basically as complicated as P3s get.

So the number of bidders will likely be limited which means the bidding will not be as competitive as it could be and therefore, as the authors suggest, the bidding consortia may be able to pad their profits.

Gov’t transaction costs

[P3] contracting can be thought of as government contracting out under unfavourable circumstances…[F]ixed-price PSA contracts can be difficult or time-consuming to enforce. However, [P3] contracts are generally much more complicated and cover a much longer time frame. Therefore, [P3] transaction costs are likely to be significantly higher than PSA transaction costs. (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

The “transaction costs” (all of the costs required to “initiate, negotiate and manage the [P3] relationship over the life of the contract”1) associated with the QEII design-build-finance-maintain contract will be high.

As Jean Laroche pointed out last week, that most recent $151 million approved by cabinet is “simply to get the design and legal documents” associated with the QEII redevelopment “ready to put to potential partners.” (Spelling out every detail “down to the exact size and speed of hospital elevators” doesn’t come cheap.)

McNeil was clear — this is a lesson learned from the great P3 schools experiment. One of the key takeaways from Auditor General Jacques Lapointe’s February 2010 report on that program was that the Department of Education’s contract management processes and procedures were woefully lacking (or as Lapointe put it, the contracts, which represented a financial obligation to the province totaling “approximately $830 million over their 20 year life” required “a very high duty of care which has not been adequately met by the Department of Education.”) Certainly, the list of government personnel (ministers and staff) already implicated in the governance of QEII redevelopment project is eye-popping.

But what if the lesson that should have been learned was not that the government should assign everyone and his cat to oversee these complex contracts but that the government should not enter such complex contracts in the first place because the transaction costs associated with them are too high?

Higher private sector financing costs

Okay, on the flip side of that last item: financing (read: borrowing) costs are lower for provincial governments than for private companies.

In fact, according to University of Manitoba economics prof John Loxley — who, back in 2012, looked at all the evaluations of P3 projects posted online by Infrastructure Ontario (IO) so you wouldn’t have to — no P3 project beat any PSA on the basis of financing costs. 2

And higher private sector borrowing costs add to the overall cost of any given project.

Partners?

Even if a [P3] had lower costs than a PSA, the private sector participants per se do not want to pass on the lower costs to government. Their primary goal is to maximize their profits. Sometimes this reality gets lost in the “partnership” rhetoric and in governments’ desire to deliver services. Private sector profit margins are a cost to government. Of course this cost applies to PSA contracts as well. The key issue is whether [P3] margins are likely to be higher. (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

If you read the first item in this list, then you know we’ve already established that P3 margins are likely to be higher than those for PSA contracts because the projects are likely to be so complex there will be relatively few qualified bidders.

That said, the authors admit it’s hard to find empirical evidence about private-sector profits in P3 deals because “firms do not publish financial data on individual projects,” but they did cite one study from the UK that found that private sector companies involved in the construction of hospital facilities in that country (the Motherland of the P3 project) earn “an excess [emphasis theirs] return of almost 10 per cent on average.” 3

On budget, on time?

It is true that the inflexibility of contracts and the financial risk transferred to the private partners have a powerful effect in keeping projects on track. However, the yardsticks by which the on-time and on-budget criteria are measured are typically flawed. The “start dates” of [P3]s are marked after the conclusion of a lengthy negotiation and project-planning process between a government and a private consortium, making project completions seem more efficient than they really are. Meanwhile, the estimated cost of a project has a tendency to increase during that preliminary process. In other words, the delay and cost inflation that so often characterize traditional PSAs are not magically eliminated in a [P3]: they just tend to occur prior to the first shovel breaking ground, rather than incrementally over the course of the project’s construction. (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

The QEII New Generation project illustrates this perfectly: the plan to upgrade what was then called “Capital Health” infrastructure (it’s now Nova Scotia Health Authority Central Zone infrastructure) dates to 2011 and the NDP government of Darrell Dexter.

The first step, announced on December 14 of that year, was to commission a “study to determine the most economical and efficient way to complete needed upgrades” to the Capital Health infrastructure. Two days later, the government announced it was also taking the “first step” in the “expansion and renovation” of the Dartmouth General Hospital, by investing in the preliminary design.

The Dartmouth General project was a government-led or public sector alternative (PSA) project, so the clock on it started running right there and then, in December 2011 — and as we know, seven years later, the work is still in progress.

But the clock won’t start ticking on the QEII Health Sciences Centre project until the construction contract is awarded, so the seven years that have already been spent on it and the time between now and the awarding of the contract won’t count.

As for the budget, well, according to 2014 cabinet documents accessed by the CBC’s Jean Laroche in 2016, the initial estimate for the work on the Halifax Infirmary, the Centennial Building and the Veterans Memorial hospitals was $251 million, although the number was “expected to swell as the scope of the project widen[ed].” The same documents put the cost for the Dartmouth General work at $132 million.

If the cost of the Dartmouth General has risen since that initial estimate, it will be seen as an example of government incompetence whereas McNeil is already signalling that the costs of the QEII revamp will likely be higher than first estimated. In other words, the “cost escalation” will have occurred before shovel ever meets ground.

In his October 4 announcement, the premier, according to The Star Halifax, said: “We’ve seen huge overruns. We believe this is the best value for the taxpayers of Nova Scotia.”

I asked David Jackson, the Premier’s Office spokesperson, what “overruns” McNeil was referring to and he told me in an email:

A recent example of a significant cost overrun is the Colchester Regional Hospital. When approved in 2005, the estimated cost was $104 million, but the actual cost almost doubled to more than $184 million (noted in 2011 auditor general’s report).

Here’s what the AG said about the Colchester hospital project:

The project to replace the Colchester Regional Hospital was approved in 2005 with a budget of $104 million. This budget was not a realistic estimate of the expected costs to build the new hospital and was not sufficient to complete construction. It was based on assumptions that were unreasonable or unsupported. It did not, for instance, consider inflation over the life of the project.

It seems to me that if you start with an “unrealistic budget,” you will end up going over it no matter what project delivery model you choose. The problem isn’t that the government had a perfectly adequate $104 million budget that it blew through utter incompetence — the problem was that it had an “unrealistic budget” (probably the result of the same reluctance to admit how much things really cost that makes governments like P3 agreements so much.)

If the hospital had been a P3 project, it is possible the budget would have been more realistic from the outset and the private companies doing the work would have stayed within it. But the end result would probably have been the same: a hospital that cost $184 million. (In other words, the cost escalation would have happened during the planning stage, not over the course of the project’s construction.)

Build now, pay later

[A] difference between a [P3] and direct government provision is the timing of the cash flows. With direct government provision, government bears large “upfront” costs and relatively low costs “over time” (typically for 30 years). In a typical [P3], government pays little or nothing “upfront” and relatively large amounts “over time.” Thus, incumbent governments can provide current users and voters with current benefits, thereby garnering political credit, while deferring costs to future politicians, future voters or users. Importantly, however, the government’s cash costs are shifted, they are not eliminated and might increase over the life of the project. (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

This is what the premier is talking about when he says opting for a P3 model for the QEII Health Sciences revamp will give his government “more flexibility for continuing with the rest of its capital plan for projects such as schools and roads.” The current Liberal government will gain that flexibility at the expense of whatever government is in power when it’s actually time to pay the bills for the QEII project.

But the bottom line, of course, is that it is the citizens of Nova Scotia who will be paying the bills no matter when they come in, and if a government feels the need to pretend it can build infrastructure without spending money or raising taxes (and if citizens to choose to believe that), some of the blame rests with us citizens. Vining and Boardman call it “fiscal illusion,” and say voters do tend to suffer from it.

VfM

Many scholars have questioned the accuracy, depth and objectivity of VfM studies. 4 (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

Part of Deloitte’s $500,000 mission was to conduct what is known as a Value for Money (VfM) study to help determine which option — P3 or PSA — made more sense for the QEII redevelopment project.

What VfMs are intended to do is “to help government officials determine if, when entering into a P3 agreement, they are likely to obtain a better deal compared to conventional approaches to procure the same project.”5

There are multiple problems with VfM studies, according to my buddies Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining (I feel like we really should be on a first-name basis by now).

One is that the consultant conducting the study may underestimate the transaction costs involved in managing and monitoring the P3 contract. Another is that the analysis may not compare “like with like.” In the case of the QEII VfM, according to Jean Laroche:

An official closely associated with the project told CBC the province provided Deloitte with 30 projects completed by the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal for comparison, including the construction of the Cobequid Community Health Centre, the Halifax Infirmary and various schools.

I would say comparing a hospital complex to a school does not qualify as comparing “like with like.” I’d go further, and suggest comparing a hospital complex to an “ambulatory care centre” (which is how the Nova Scotia Health Authority describes the Cobequid Community Health Centre) doesn’t necessarily qualify as comparing “like with like” but I guess it will pass with a push.

There are two other problems with VfM studies that seem particularly worth noting, but they’re complicated so I’m going to separate them into two short items so you’ll hardly even notice you’re reading them:

VfM: Discount rate

VfM studies often use what Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining term “inappropriate discount rates.” So, what’s a discount rate? Let’s use the example of the QEII redevelopment:

Let’s say to undertake the QEII project by itself, the NS Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal would have to borrow $1 billion up front (I just made that figure up, we don’t know yet how much the project will cost) and pay it back over 30 years.

On the other hand, if it awarded the contract to a private consortium through the P3 agreement outlined by the premier, it would pay nothing up front, then pay half the project’s $1 billion cost when construction was complete, then make regular payments to the consortium over the following 30 years.

To compare the two options, the government has to convert those future payments to present values and to do that, it uses a discount rate which “effectively represents the ‘exchange rate’ between present and future sums of money. It is a percentage by which a cash flow element in the future (i.e., project costs and revenues) is reduced for each year that cash flow is expected to occur. ”6

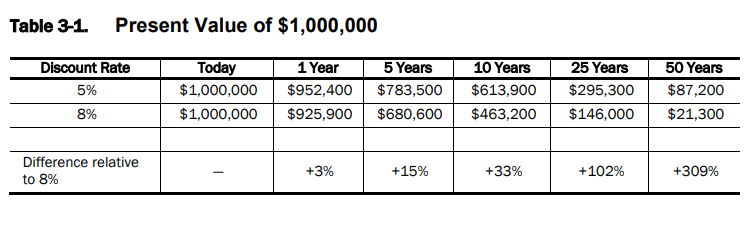

As you can imagine, the discount rate you choose matters – in fact, over a 30-year period like the one we’re talking about for the QEII project, the difference between a 5% discount rate and an 8% discount rate is downright startling:

Source: “Value for Money Assessment for Public-Private Partnerships: A Primer” (2012), US Department of Transportation, Federal Highways Division

Basically, choosing a higher discount rate over a 30-year period reduces the present value of the costs associated with a P3 project considerably, and generally makes the P3 model look like better value than the PSA model.

University of Manitoba economics professor John Loxley gives the real-life example of British Columbia’s Abbotsford Hospital, where “a 6% discount rate was used to show VfM of $39 million or 8.4%, which would have fallen to $13 million or 2.8% had a 5% discount rate been used.” 7

We don’t know what discount rate Deloitte used in its VfM for the QEII redevelopment project because we’re not allowed to see the VfM.

But the instructions to Deloitte (found in the tender documents) at least seem to recognize VfMs as problematic:

Respondents are asked to identify risks that may be associated with a value for money analysis, results of critical evaluations elsewhere and how they will mitigate the risks and adjust their approach to ensure a higher level of objectivity, accuracy and reliability.

VfM: Risk transfer

One of the big selling points for P3 agreements, according to Loxley, is the private sector’s “superior ability to deliver value for money through economies of scale, more efficient and innovative use of labour and materials, and the transfer of risk.” (Risk of cost overruns, for example, which the private sector is expected to assume in the QEII P3 deal.)

Loxley looked at the VfM assessments for individual projects posted online by Infrastructure Ontario (IO) and discovered that virtually every one of those published “purport[ed] to demonstrate that the [P3] option is superior.”8

But when he looked more closely, he realized that the P3s’ superior performance was always down to the value of risk “said to be transferred from the public to the private partner.” Moreover, in the Ontario examples, Loxley says it’s not clear “what risks are being transferred” and IO’s risk analysis is based on a consultant’s report which gives “no source, reference, or justification…for any one of its numbers.” 9 Writes Loxley:

If these crucial risk transfer numbers have any foundation empirically, it is not clear what it is or where it comes from.10

What he’s saying, as crazy as it may seem, is that the key number — the one that swung the argument in favor of the P3 option — was apparently pulled from thin air. So, what value did Deloitte assign to risk transfer in its evaluation? Again, we don’t know because we aren’t allowed to see the report.

One final word on risk from Vining and Boardman. In the wonderfully titled, “Self-interest springs eternal: Political economy reasons why public-private-partnerships do not work as well as expected,” they note that private sector companies don’t particular want to take on risk — and sometimes “turn out to be more risk-averse than public-sector participants had expected.”

[F]irms often require high premiums to accept risk or may not be prepared to accept certain kinds of risk at all. Of course, they will be unable to obtain a high risk premium if the bidding process is highly competitive, but often it is not, due to numerous barriers to entry…11

The Consultocracy

[P3s] also often provide political benefits by channelling financial benefits to aligned interest groups, such as law firms, merchant banks, large construction firms and consultants, labelled by Hodge and Bowman 12 as the “consultocracy.” (Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016)

It remains to be seen which banks and construction firms will benefit from this latest P3 experiment, but the consultants are already at the trough table: feasibility studies, pre-design studies, a master plan drafted by an Ontario company with the assistance of “seven Nova Scotia consulting firms,” a study to determine the best delivery option for the project, government officials “working with consultants” to ensure every detail of the P3 contract is “crystal clear,” and the list, no doubt, goes on.

Ideology

One final note on P3 projects: a number of commentators noted that some governments prefer the P3 model for ideological reasons. (The example I saw cited was that of former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper whose government required that all projects with eligible costs over $100 million undergo a P3 assessment to qualify for federal infrastructure funding.)

John Loxley argues that when governments say they can’t afford to spend on infrastructure, they are often responding to “self-imposed” constraints — like balanced budget legislation and “the systematic, neoliberal reduction of taxes over the last decade.”13

Further, he says that believing the “microeconomic” arguments in favor of P3s — chiefly, that the private sector has a superior ability to deliver value for money — is to “ignore the link” between that largely self-induced macro fiscal restraint and “the erosion of public-sector capacity” and to accept the “ideological presupposition that the public sector is inherently less efficient and less competent.”14

I don’t find it difficult to believe that the pro-business McNeil government, which has embraced austerity like a long-lost relative, would likewise embrace the P3 model out of the same sort of ideological fervor.

That he won’t let us see the Deloitte report which (apparently) justifies the decision to use a P3 model for the QEII project does nothing to convince me otherwise.

Note: Lots of people are writing interesting things about the QEII P3 deal, including Stephen Kimber, Christine Saulnier and the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE)

[signoff]

- Boardman, Siemiatycki and Vining 2016

- J. Loxley, ‘Public-Private partnerships After the Global Financial Crisis: Ideology Trumping Economic reality’, Studies in Political Economy, August, 2012.

- V. Vecchi, M. Hellowell and S. Gattic, “Does the Private Sector Receive an Excessive Return from Investments in Health Care Infrastructure Projects? Evidence from the UK,” Health Policy 110, 2-3 (2013): 243-270.

- D. Heald, “Value for Money Tests and Accounting Treatment in PFI Schemes,” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 16, 3 (2003): 342-371; Edwards et al., Evaluating the Operation

- “Value for Money Assessment for Public-Private Partnerships: A Primer” (2012), US Department of Transportation, Federal Highways Division

- “Value for Money Assessment for Public-Private Partnerships: A Primer” (2012), US Department of Transportation, Federal Highways Division

- Loxley 2012.

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- A. Vining, A. Boardman, “”Self-interest springs eternal: Political economy reasons why public-private-partnerships do not work as well as expected,” 2014

- 1 G. Hodge and D. Bowman, “The ‘Consultocracy’: The Business of Reforming Government,” in Privatization and Market

Development: Global Movements in Public Policy Ideas, ed. Graeme Hodge (2006), Chapter 6. - Loxley, 2012

- ibid